Zuzana Fačkovcová, from Slovakia, visited the Lichen Collection of the Hungarian Natural History Museum to study Solenopsora candicans and find out whether genetic diversity of photobiont in this model lichen matches the genetic diversity of the mycobiont across its distributional range. We interviewed the young and dedicated researcher about her studies and lichens in general before the defence of her PhD in summer. By now, Zuzana is employed by the Plant Science and Biodiversity Centre of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, in Bratislava.

Could you tell us more about your research in general?

My research focuses on the topics of evolutionary biology, ecology, and phylogeography of lichens. I am also interested in biomonitoring with lichens.

Actually I am combining genetic and ecological data, to understand the evolution of lichen species across several geographical areas throughout Europe. I am trying to elucidate whether symbiotic interactions in lichens play any role in shaping their distributional range.

Lichens are interesting objects for this purpose, since they represent a specific and complex symbiotic association between a fungus, called “mycobiont”, and a compatible photosynthesizing partner – either algae or cyanobacteria, called “photobiont”.

Not so long time ago we could have read about a study which states that more than 50 species of the lichens might consist of symbiotic association of not only two but three partners. Could you tell us more about it?

Yes, this was one of the most important discoveries since 1868, when the Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener revealed that the lichens are symbiotic organisms comprising fungus and algae. This longstanding “dual hypothesis” has been reconsidered after recent discovery that not only one fungus participate to the lichen symbiosis. A third symbiotic partner (basidiomycete yeasts incorporated in lichen cortex), has been detected as stable component in many lichen species. The certain genetic lineages of basidiomycete yeasts were identified to be related to specific lichen species across six continents. Moreover, interesting finding was that the presence of some secondary metabolites was associated with abundance of basidiomycete yeasts suggesting that they can play a role in forming a complete, functioning lichen thallus. With this discovery, many new questions were opened and thus further investigation is needed.

What is the aim of your Synthesys visit here?

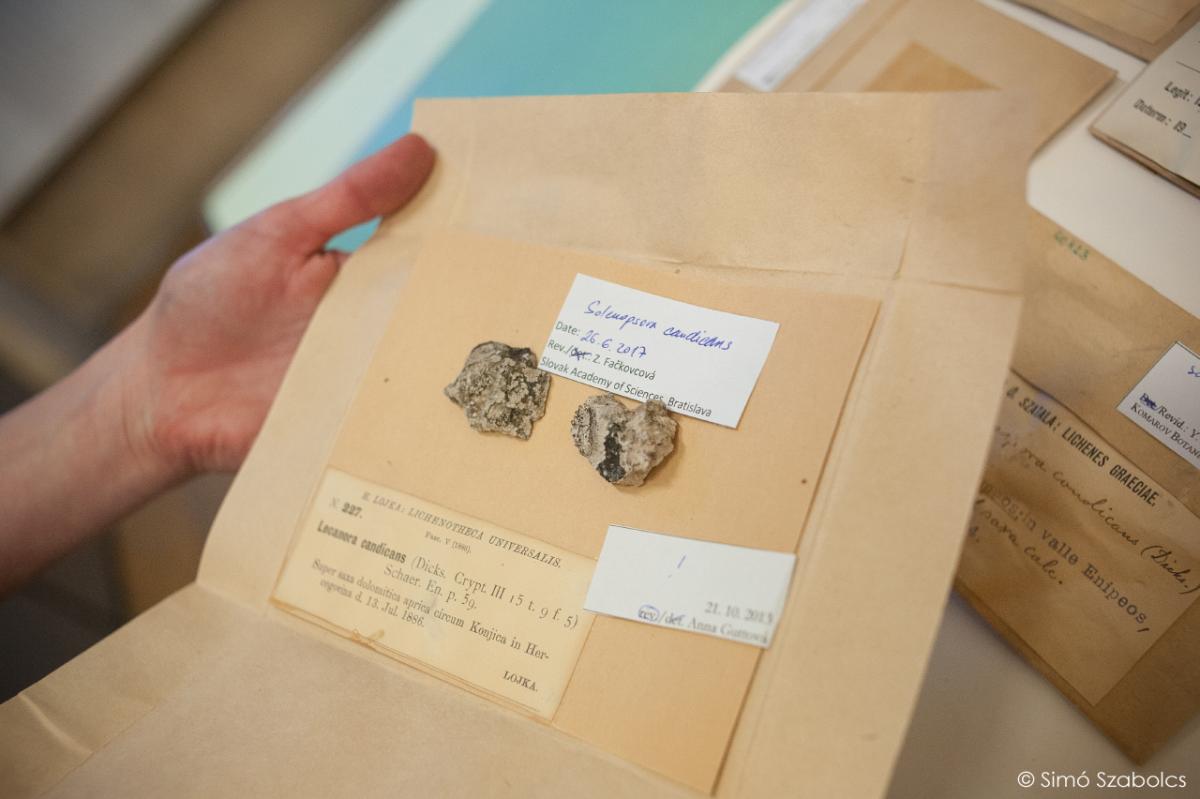

I came to visit the Natural History Museum to do a revision of the herbarium collection focusing on the lichen genus Solenopsora. I extracted DNA from selected specimens which I will use for further analyses. Since one mycobiont can associate with different photobionts across geographical regions or under different ecological conditions, I would like to find out, whether genetic diversity of photobiont in model lichen Solenopsora candicans matches the genetic diversity of the mycobiont across its distributional range. In particular, I study their genetic structure across the range: Mediterranean – Pannonia – Western Carpathians.

The lichen Solenopsora candicans (Dicks.) J. Steiner on calcareous rocks in Malé Karpaty Mts., Slovakia (photo: Zuzana Fačkovcová)

Which are the main biological characteristics of lichens and what kind of features do you examine?

The lichen body (thallus) has morphological and physiological traits that are novel for the symbiotic state and are not known from the separate components. For example, unlichenized mycobiont remains quite amorphous when cultivated separately in laboratory conditions, while in a natural symbiotic state a well-structured thallus is developed. The lichens can be regarded as an intrinsically self-supporting ecosystem, where the photobiont provides carbohydrates through photosynthesis and the mycobiont provides some sort of protected environment for photobionts. Lichens are poikilohydric organisms, which means that they do not regulate water content in their thalli actively. When wet, they absorb water as a sponge and when dry, they tolerate dehydration and can be desiccated fast without physiological damage. I focus especially on genetic features of lichens – on variation of DNA in both symbionts.

More than a 130-years old specimen of Solenopsora candicans

Could you tell us more about the morphology of the lichens? How can you identify them in field and in laboratory?

The lichen body (thallus) forms a wide range of morphologically diverse structures. The most common three types of thallus are the fruticose, foliose and crustose. The fruticose thallus looks like a small shrub or branches usually attached to substrate only at one point. The foliose lichen is leaf-like, composed by several small or bigger lobes attached to the substrate at more points, and the crustose thallus forms patches or crusts closely attached by its whole lower surface. Some species can easily be recognized in the field, however, laboratory equipment is neccessary for the identification of most of the lichens. We observe various anatomical features under microscope, such as type and size of spores, thickness of particular thallus layers, etc. Since lichens produce secondary metabolites which can be species specific, we also use several chemical substances to identify these metabolites and based on their presence or absence to identify the species.

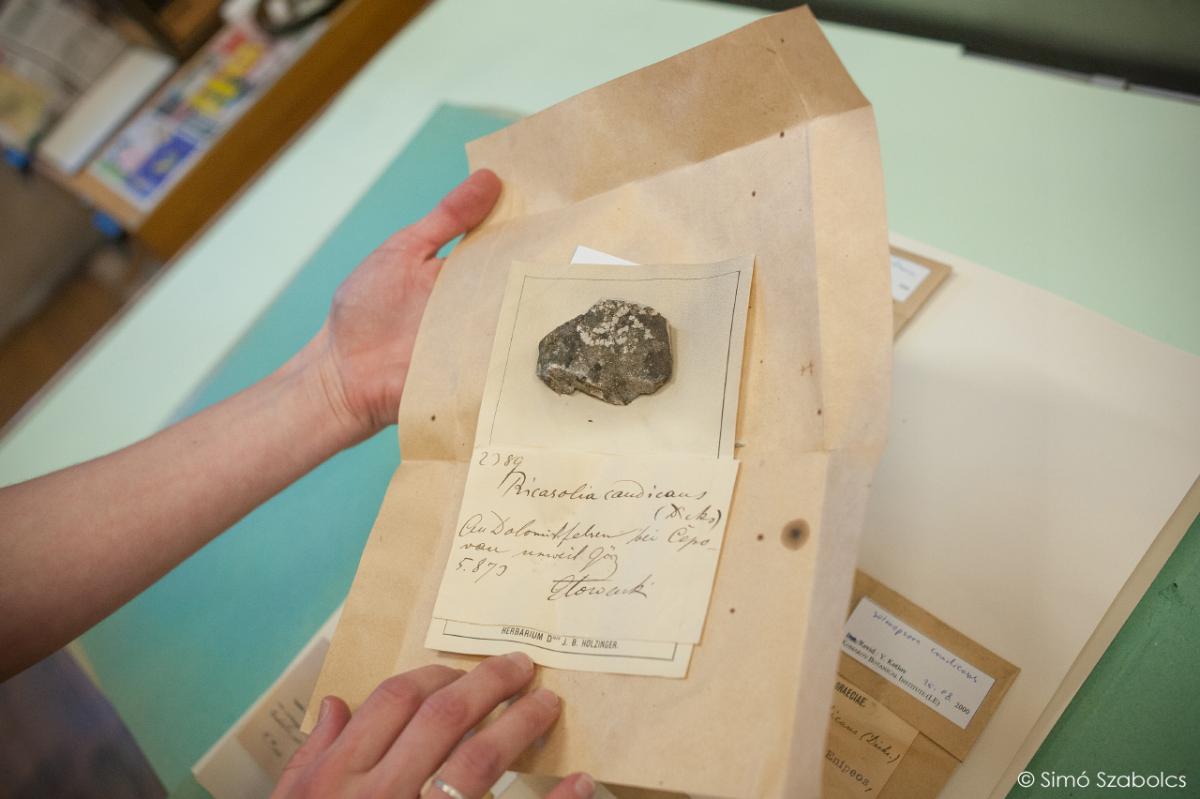

The specimen of Solenopsora candicans named according to old synonym – Ricasolia candicans (Dicks.).

So being a lichen specialist you also have to be familiar with fungi and photobionts.What is the difference in the research methods?

Fungi, algae, and cyanobacteria belong to three different kingdoms and thus it is necessary to consider their specificities when preparing the design of a specific study. For example, concerning genetic studies, different markers can be analysed since the photobiont,besides nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, also contains chloroplast DNA, which is missing in the mycobiont. Each marker provides slightly different type of information, thus the selection of the appropriate marker depends on the research questions which are addressed. This is true also for ecophysiological studies, where for example we can assess the photosynthetic performance of the photobiont, or content of ergosterol in the mycobiont, as indicators of their vitality.

What drives the reproduction of lichens? Do fungi and photobionts start to reproduce at the same time?

There are several peculiarities concerning the reproduction of lichens. In spite of free-living algae or cyanobacteria can reproduce sexually, this ability is suppressed within the lichen symbiosis and only the mycobiont reproduces sexually via asco- or basidiospores. After releasing spores into the environment, they germinate and have to associate with compatible photobiont partners to establish the lichen symbiosis. This ensures genetic variation, but can be complicated if an appropriate photobiont is missing at a certain site. On the other hand, vegetative reproduction involves both partners together. There are specific structures, e.g. soredia, isidia, schizidia, or fragments of thalli already comprising mycobiont and photobiont cells, and thus they are released and dispersed to the environment together.

The lichen Solenopsora candicans growing on sandstones close to the Atlantic ocean (Foz do Lisandro, Portugal) (photo: Zuzana Fačkovcová)

Which areas do you examine lichens from? Are there any differences according to geographic distribution?

In my research, I focus especially on species confined to Mediterranean-type climate covering Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor. However, the unique characters of symbiosis facilitate lichens to occur in a wide range of habitats throughout the world, even in those where the single partners would not be able to survive. Thus, we can find lichens in almost all terrestrial habitats, from tropical to polar regions. Some of them have wide distributional ranges, whereas the others are restricted to smaller geographical areas. However, comparing to vascular plants, endemic lichens are much scarce.

Locality of Solenopsora candicans in Malé Karpaty Mts., Slovakia (photo: Zuzana Fačkovcová)

Why is the Lichen Collection of the Hungarian Natural History Museum special for you? Which are your favourite specimens or discoveries here?

Hungarian Natural History Museum preserves an extensive collection of lichens from Pannonia, adjacent countriesand also from other continents. It is a unique collection gathered by great biologists working in this area in the past (e.g. Timkó, Kitaibel, Degen, Lumnitzer, Hazslinszky, Lojka, Gyelnik, Szatala) or in the present (e.g. László Lőkös, - the curator of the Lichen collection of the HNHM- editor). I revised herbarium material confined to Solenopsora taxa. I have already revealed more than one hundred specimens belonging to this genus. More than half of them were found among unidentified material and represent new records to the regions or even to the countries. I like especially those specimens collected in Albania since we have not had any data about the presence of the genus there so far.

What is the ecological role of lichens? How do they indicate air pollution and are they vulnerable for climatic or microclimatic changes?

Lichens play a significant role in ecosystems. They contribute to mineral cycling, nitrogen fixation and are an important component of food chain, especially in polar regions, where they dominate. As first colonizers of new habitats they contribute to bedrock weathering and development of soils. The thalli also provide shelter for small invertebrates and source of nest-building material for birds. The equilibrium between symbionts in lichen thallus is very sensitive to natural or anthropogenic disturbances, including climatic changes as well as air pollution. They are able to accumulate heavy metals and other pollutants from the atmosphere. In the past, lichens suffered from increasing amount of sulphur dioxide in the environment, whereas nowadays we observe increasing eutrophication. The most sensitive are the fruticose epiphytic lichens, which are widely used in biomonitoring studies. The presence of several sensitive species well reflects the quality of the environment.

Happy findings – Solenopsora candicans on rock in Germany (photo: Viktor Kučera).

What can you do for the protection of lichens?

When protected areas are established, lichens, as well as mosses (and many understudied groups) are often neglected. In fact, compared with vascular plants, only few lichen species are legally protected. In the case of lichens, especially for small and scarcely known species, we must protect the habitat and the whole structure of ecological communities, to protect the species. This would also ensure the protection of less apparent organisms. Umbrella species (i.e., species whose conservation results in many other species being conserved at the ecosystem level) are of paramount importance for this purpose. Furthermore, botanists and in general plant collectors (fascinated by rare samples interesting for their study!) can be a serious threat to the survival of rare species and thus lichenologists must be conscious in the field.

What is your overall opinion about your Synthesys visit?

First of all, I would like to aknowledge the Synthesys grant for the financial support of my project and the staff members for their kind hospitality and creating perfect working conditions. By visiting the Natural History Museum, I have gathered significant data for the future research. I have obtained new information about species distribution, visited molecular laboratory where I have prepared DNA extracts from specimens crucial for the genetic study. I am also very glad for establishment of collaboration with the curator of herbarium, Dr. László Lőkös who is also collector of huge amount of Solenopsora specimens deposited in BP. As a result, we will prepare a paper about new records of Solenopsora species in the Balkan Peninsula.

Could you tell us more about your future plans?

After my PhD. defence in August, I will be employed at the Plant Science and Biodiversity Centre, Slovak Academy of Sciences, in Bratislava. I will continue with genetic and ecological research referring to evolutionary topics and I will investigate potential coevolution among lichen symbionts. Moreover, in parallel, I would like to continue with biomonitoring studies.

Written by: Bernadett Döme, Krisztián Kucska

Photos: Szabolcs Simó, Zuzana Fačkovcová, Viktor Kučera