Alfréd Dulai has been the director of the Department of Palaeontology of the Hungarian Natural History Museum since 2010. Being a geologist, he researches invertebrate fossils of the seas but also participates in scientific publications. We asked him about his career, professional activities and everyday life.

When did you start to be interested in natural sciences?

I went to a chemical industrial high school in Kazincbarcika, and there was a teacher, János Hír who inspired me to learn palaeontology. He had just got to our school as a biology and geography teacher and he had also been working on archaeological research in the caves of the Pongor-lyuk in Répáshuta, where he took us with himself. We found remains of brown bears and other vertebrates there. I became so enthusiastic about explorations, that I applied to the ELTE University to study geology.

János Hír did not stay in the school to teach for a long time. He left for the Museum of Pásztó and has been the director of the institution since then.

How did you get to the Hungarian Natural History Museum?

We basically studied about the invertebrates under the subject palaeontology in the university, therefore my interest turned to that group of animals. In the first grade I joined a project, the target area of which was the Lókúti Hill, where we collected Low-Jurassic brachiopods. The great chance of mine came in the year of my graduation, when Zoltán István Nagy retired from the Department of Palaeontology and Geology of HNHM. The chance to be employed by a museum or any other research institutions is quite little.

What do you do exactly? Could you tell me more about your job?

In this Department, the objects of our work are primarily the different groups of fossils, which we examine in terms of geology, as well. Currently, my research fields are the seawater invertebrates, particularly the brachiopods. I wrote both my graduation and doctorate thesis about the Jurassic brachiopods of the Transdanubian Mountains. When I started to work in the HNHM, I was appointed as the curator of the Miocene Collection. Apart from the brachiopods, I have researched Bryozoa and Polyplacophora.

Do you enjoy your work? What do you like about it the most?

My job is my hobby, as well. It is very exciting to be the first to find remains of creatures of old times, which have been enclosed in rocks for millions of years. When I collect a specimen, I do the preparation work in the laboratory, and then I identify it. After we have finished the processing work of a certain deposit or locality, we can form an idea about the zoological community of that age and determine the time and environment they could have lived in. The experience of discovery and scientific investigation is very important for me.

Why do you consider your activities as important?

Our aim is to learn more about the nature of the olden times as well as our own past. In addition, the information we gain from determination and environment reconstruction can be effectively applied in research of raw materials. In Hungary, it was particularly true for coal and bauxite mining in the past. Now the most important field where paleontological studies are used is the hydrocarbon exploration. During the deepening of drilling, fossils can determine which age or deposit we are in and if it is worth continuing to drill down deeper. The slightest mistake of palaeontologists can cost millions. Apart from the practical use, our examinations belong to the so called basic research, primary aim of which is to obtain new information and more knowledge in each topic.

Apart from the research work there must be lot of jobs in the museum. What do you do as the director of the Department of Palaeontology and Geology?

This Department does not belong to the larger ones of the institution; we only have a few museologists. But the number of staff is not small, we have retired colleagues as volunteers and guest scientists who work here within the frameworks of different projects. A part of the MTA-MTM-ELTE Research Group for Palaeontology[1] financed by the academy also works here. All in all, I have to coordinate the works of many people.

Being the director of the Department is an endurable job, as I basically care about the collection and research. However, it has not completely been true in the last two or three years. We had to move our collection due to the reconstruction of our building (Ludovika), and it totally rescheduled our daily routine.

[1] The abbreviations cover three significant scientific institutions.

MTA: Hungarian Academy of Sciences

MTM: Hungarian Natural History Museum

ELTE: Eötvös Loránd University

What are you interested in besides your research field?

I work on scientific dissemination a lot relatively. Making exhibitions, guiding there and the collection, all accompany the job of a museologist; all of them belong to the subjects of scientific dissemination. However, I prefer writing articles. I regularly publish in the two leading Hungarian scientific periodicals and in columns of a very popular online magazine.

Which scientific field are you interested in except for the geology?

I could not name any. The geology has completely filled my life.

Table decorated with ammonites engravings. It is always used by the current director of the Department.

What do you do in your free time?

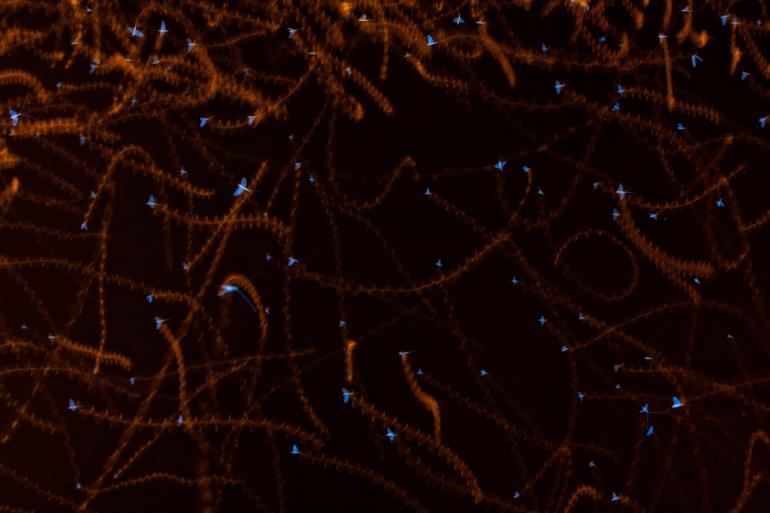

For me, my family is the most important thing. We live in Szentendre and I go to work from there so it takes up two and a half hours apart from the eight hours work-time every weekday. When I get home the day is over, so I can spend quality time with my family only at the weekend. We go to hike together quite often as my son is really interested in taking nature photos. His photo „On the way of Polymitarcys virgo” won an award as the natural photographer of the year and it was also exhibited in our museum.

„On the way of Polymitarcys virgo” (photo by Dávid Dulai)

What is your favourite object of the collection?

We have hundreds of thousands of inventoried items; the total number is in the millions, so it is difficult to choose one of them. The favourite is always the one I am working on. Recently, I have been working on micromorph brachiopods, so I spend most of my times with sitting at microscopes.

Miocene micromorph brachiopods from the Mecsek

What are your plans for the future?

Although I am not old, I have already accumulated so much material and incomplete topics that I would have work to do for years even if I didn’t collect any more specimens. While my aim is to completely work up the material we already have, I would not give up on the beauty of the field work. Palaeontologists are hardly able to stop collecting activities. One of my colleagues says we should not collect after we reach 40 years of age because we never will be able to complete the processing work. However, nobody can stop. In the next 4 years, our main project along with an international research group is to work up the Eocene drilling material that our museum has preserves for more decades. Apart from that I would like to investigate our Mesozoic (Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous) micromorph brachiopods in close details. They used to be unreleasable from the carbon rocks, but recently we have been able to see them more often due to an acetic acid solution.

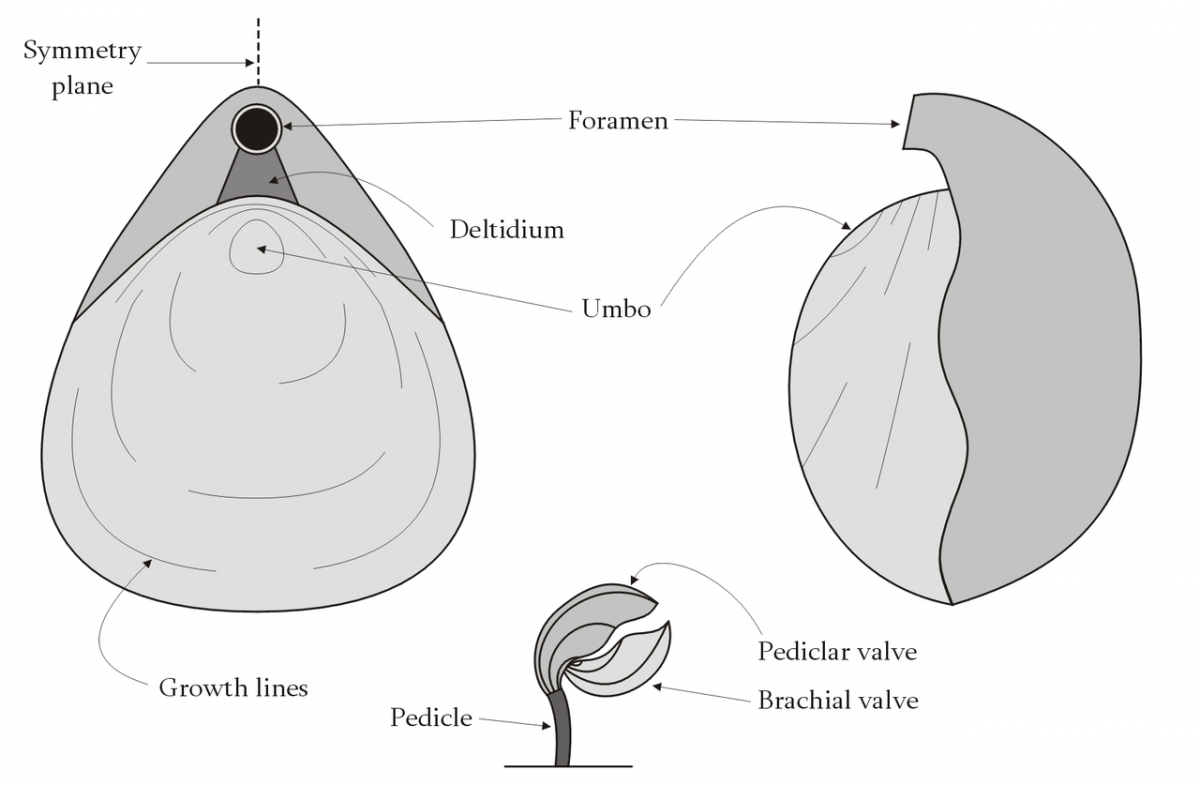

The brachiopods are marine invertebrates. Although they are very similar to the bivalves, their internal structure is completely different, thus they belong to different phylum. They stabilize themselves to the solid ground by their pedicles and filter food from the water by a lophophore ciliated tentacle crown). Their role was significant in the history of Earth, particularly in the Palaeozoic Era and some periods of Mesozoic Era. In Hungary, they are frequently found in Jurassic and Triassic rocks and they often occur at Eocene, Oligocene and Miocene localities.

The structure of brachiopods

Writer: Krisztián Kucska

Photo: Szabolcs Simó

Translation: Bernadett Döme